Encephalitis: how researchers are making numbers talk

Date:

Changed on 25/10/2022

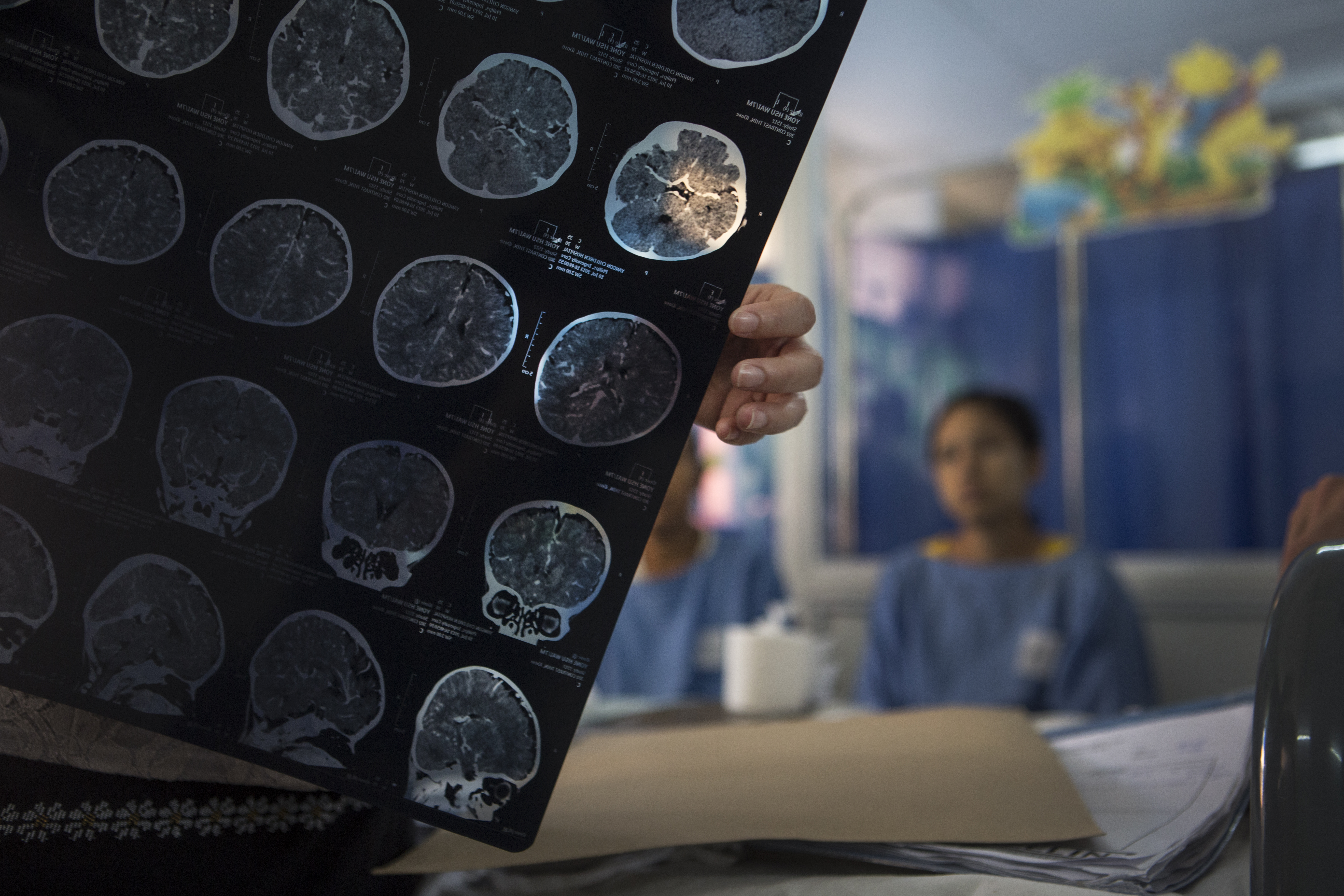

This study [1] was the biggest of its kind to date, lasting three years. It focused on 694 children admitted into hospitals in four countries in the Greater Mekong region: Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Myanmar. A harmonised diagnostic procedure made it possible to determine that 664 of these young patients indeed had encephalitis. This acute inflammation of the cerebral tissue may result from many causes. Hence the importance of correctly identifying the pathogenic agents at the source of the disease, whether they are already known or yet to be discovered.

Coordinated by Institut Pasteur as part of the South East Asia encephalitis consortium, this research has shown that 33% of cases were caused by the Japanese encephalitis virus.

The SEAe consortium

The SEAe consortium includes the health authorities and hospitals of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar and Vietnam, Institut Pasteur, Institut Pasteur du Cambodge, National Institute of Hygiene and Epidemiology Vietnam, Inserm, Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD), National Research Institute for Sustainable Development (IRD), Aix-Marseille University, École des Hautes Études en Santé Publique (EHESP), and the Wellcome Trust Oxford MOP network for South East Asia. TotalEnergies Foundation and members of Aviesan Sud contributed to funding for this project.

But researchers also found cases related to the viruses for dengue fever, influenza, herpes simplex 1, pneumococcus, and Enterovirus 71, as well as around thirty other infectious agents, not to mention some with autoimmune causes as well. From a clinical point of view, known treatments can currently respond to 18% of cases studied. However, vaccination could prevent 42% of all these infections. That is the major takeaway from this study, which promises to have a significant impact.

At the Inria Saclay Centre, researcher Kevin Bleakley is part of CELESTE, a joint project-team (Inria, Inria, Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS) with a mathematics focus, working at the interface between statistics and artificial intelligence. He was also the statistician for this medical study. “Beyond the theoretical work that we usually carry out, I wanted to do statistics that would be immediately useful in today’s world. I have long been interested in applications in biology. I first approached researchers at Institut Curie. They put me in touch with colleagues at Institut Pasteur. That was how I started to work with them. First on dengue fever, in Cambodia. Then on encephalitis.”

A fundamental problem persists with this disease. “Researchers have difficulties identifying the causes. Especially since the affected countries are not very wealthy. Often, hospitals cannot test patients for all known pathogens.” The study made it possible to deploy exhaustive screening. “Out of 664 sick children, we were able to identify the pathogens responsible in 425 cases. Unfortunately, in the other 239, the source of the disease remains unknown. We tried many avenues. But we did not find anything conclusive.” The scientists looked closely at the children’s environment. Does the family have pigs? Ducks? Chickens? Did they live under a thatched roof? A tiled roof? A metal roof? All these parameters became variables in the statistical model.

Verbatim

There is a relationship between the number of variables taken into consideration and the number of individuals studied. The more variables of interest (blood type, blood pressure, animals in the home environment, etc.) there are, the more patients you need to be able to trust our statistical results.

Auteur

Poste

Researcher in the CELESTE project team

One of the limitations of this kind of study is the size of the sample. “664 people is a lot in the eyes of biologists. They have to spend a lot to organise screening at this level. But biostatisticians prefer larger samples. Say... 3000 people, for example.” Why? “Because there is a relationship between the number of variables taken into consideration and the number of individuals studied. The more variables of interest (blood type, blood pressure, animals in the home environment, etc.) there are, the more patients you need to be able to trust our statistical results on the connections between certain variables and a variable of interest, such as whether a child develops acute or mild encephalitis, for example. An extreme counter-example: “If we only had three patients, aged 5, 15 and 16 years old, and only the 5-year-old suffered from a severe form of the disease, we could wrongly conclude that age is an aggravating factor (possible connection between ‘young’ and ‘severe’). But in reality, this small sample is not representative. The same phenomenon could occur if we had 300 variables for only 664 children.”

For Kevin Bleakley, the idea was also to test certain methods through this study that could potentially ‘detect’ unknown causes of encephalitis. One example is Principal Component Analysis (PCA). “With this method, we projected the data in the form of points in a two-dimensional space. We then tried to highlight clusters of points corresponding to patients for whom we did not know the origin of the disease. When a cluster appeared, we could start to investigate. Try to identify variables of interest. Does age play a role? Are the children in question located in the same country? Etc. These initial elements can provide avenues for biologists to dig deeper.” Unfortunately, even with techniques that are more advanced than PCA, the results did not prove to be conclusive. “I was hopeful. But as it happens, we didn’t find anything new. This part of the research was not published as, alas, it did not deliver useful biological results.”

Verbatim

These algorithms can give incredible predictive results. That said, for them to work, they often need an enormous quantity of data.

Auteur

Poste

Researcher in the CELESTE project team

Another major part of the study concerned detection via multivariate modelling of variables closely connected to severe encephalitis in children. This kind of modelling involves predicting severe encephalitis ‘in advance’ through machine learning or artificial intelligence. Kevin Bleakley mainly worked with the ‘random forest’ AI method, “even though the quality of predictions from the study data was not superior to that of logistic regression, an ‘old-fashioned’ method that is still very popular among biologists as it is easy to interpret.”

What about neural networks? “These are quite old too. They date back to the 1950s. But the main thing that was missing back then to make use of this method was processing power. We have that now. So these algorithms can give incredible predictive results. That said, for them to work, they often need an enormous quantity of data. In the encephalitis study, we did not have such volumes. At the end of the day, there is no obvious reason why neural networks would work better than random forest or logistic regression for our sample size.”

Just another reason in support of more studies in this area with larger cohorts. It is not a hard case to put forward, considering that Japanese encephalitis alone affects around 50,000 children each year in the Greater Mekong region.

[1] Childhood encephalitis in the Greater Mekong region (the South-East Asia Encephalitis Project): a multicentre prospective study, by Jean David Pommier, Chris Gorman, Yoann Crabol, Kevin Bleakley, Heng Sothy, Ky Santy, et al., The Lancet Global Health, July 2022.