Upkie, the open-source robot that opens new avenues for training and collaboration

Date:

Changed on 20/03/2025

In 2019, new, more efficient motors appeared on the market at a relatively reasonable cost. These motors, more powerful than the "brushless" motors used until then (for example in drones), but less powerful than those used in industrial robots such as the Boston Dynamics Atlas, paved the way for the creation of intermediate-sized robots.

At the same time, the growth of an open-hardware and open-source community has made robotics more accessible, considerably reducing the barriers to entry for robotics enthusiasts and offering scientists an interesting alternative to commercial, closed and expensive robots, which limit access to a deep understanding of how they work.

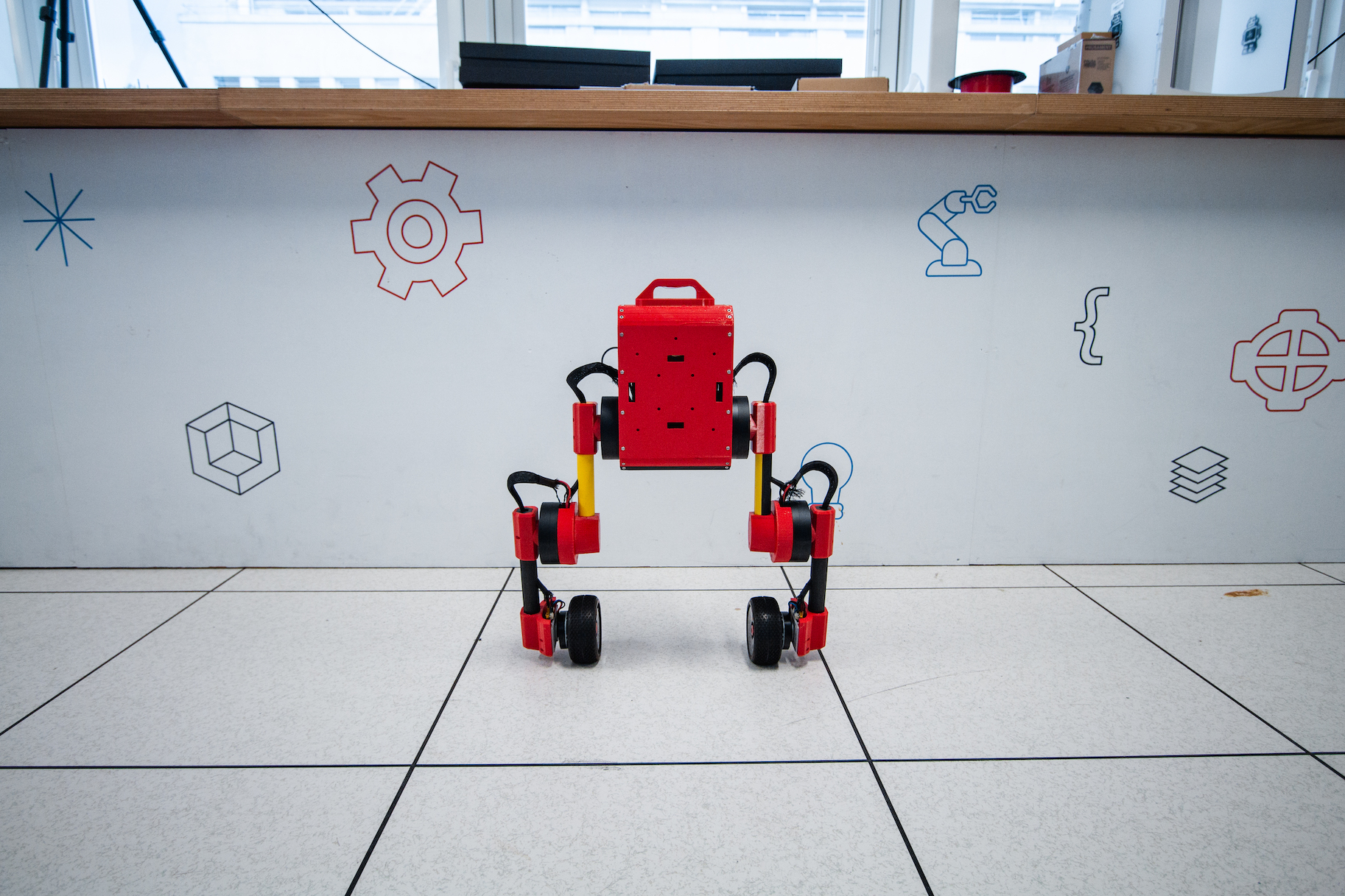

It is in this context that Stéphane Caron (WILLOW project team at the Inria Center in Paris) is developing Upkie, an 80-centimeter, 5-kilogram robot that is entirely open-hardware and that anyone could build, study and modify. Designed to be assembled with components available online and 3D printed parts, Upkie moves on two wheels and ensures its stability by relying on open-source robotics software.

Far from the heavy and expensive robots they used to handle, Upkie is quickly becoming an ideal teaching aid for doctoral students. Young researchers have in their hands a robot that they can really take ownership of, dismantle, reprogram, while putting into practice complex algorithms that they discover in manuals or in the laboratory.

Verbatim

A few years ago, we were learning algorithms on heavy and fragile robots. It was long and we had few samples. With Upkie, the barrier to entry is much lower, the robot is more accessible. This allows us to apply, on the one hand, the results of our research, but also to gradually tackle more complex problems.

Auteur

By starting with a medium-sized, low-complexity robot (six motors), PhD students can gradually familiarize themselves with the basics of biped robot control before moving on to more complex systems, such as 30-motor humanoids.

“Unlike commercial robots, we can look into the code thanks to open source. So we are never stuck when things happen that we don’t understand. We can also break it, and students don’t hold back! This is important for seeing the robot’s limits and learning to quickly iterate on ideas. But the advantage with this type of robot is that broken parts can be reprinted in 3D and replaced, at a lower cost,” adds Stéphane Caron.

The project, which has continued to evolve since its first iteration at the end of 2021, is set to grow as the community’s needs evolve. "We are now working on the connection between robotics and artificial vision. On the hardware side, we also have extensions coming, such as adding additional limbs to give the robot new capabilities," says Stéphane Caron.

In addition to training, another aspect is at the heart of the concerns of the WILLOW project team researchers for Upkie: its reproducibility.

Traditionally, it is indeed difficult to compare the results of one team to another, because the robots developed and used are different, and the algorithms often tested in specific contexts. By allowing other researchers to build their own versions of Upkie and share their results, the project proposes forms of standardization, enabled by open source, and therefore a common framework for comparing research results and algorithms.

Verbatim

One hope we have with the open-source and open-hardware aspect is that if it becomes really easy to rebuild the robot, comparisons can be made with the same code and the same software base, allowing us to know for example which algorithms are more suited to which task.

Auteur

The transparency offered by open source also allows researchers to understand exactly how robots work, and to improve algorithms without being limited by proprietary systems. "The open source side must allow everyone, industrial, academic, and individuals, to maintain understanding and access to the technology. We want to contribute to this ecosystem," he concludes.